Historical Background

During the Second World War, between 1939–1945, Polish landowners who had their estates in the General Government found themselves in the best situation. Those Polish landowners whose estates were in the Western territories of the Second Republic of Poland were treated in a violent manner—the most active ones were arrested and murdered in executions or placed in concentration camps. The remaining landowners were forcibly deported to the General Government. The GG became inhabited by landowners from the Poznań Province and from Pomerania (Pomorze) as well as by refugees from the Eastern Borderlands (Kresy Wschodnie) under Soviet occupation. In the General Government, the elimination of the landowner social stratum, as a group which could play the leading role in national resistance, was postponed by the occupier until the end of the war for economic reasons.

The Polish manor house once again, just like in the 19th century, had to take on numerous responsibilities. Landowners welcomed expropriated landowner families and exposed underground activists to their estates; they brought help to the underground army and supported clandestine education.

“When the Germans took control over the Poznań Province, their party and police authorities initiated organized terror. In mid-October 1939 in nearly every county the Germans arrested dozens of prominent people—priests, landowners, merchants, social activists, etc. Their arrest did not last for a long time. After a few days the so-called Mord-Kommando would arrive, bring them to a fake trial, during which they would face such absurd charges as ‘crimes against Germanhood,’ and the sentence was death by shooting. My uncle [Edward Potworowski] was arrested on October 19. He and thirty other ‘hostages’ were executed in the market square in Gostyń on October 21, in front of a crowd of Poles had to watch it […] ‘. [Dezydery Chłapowski, Potworowscy. Kronika rodzinna (Potworowskis. A Family Chronicle), 2002].

“[…] the resettlement of Poles from the Poznań Province to Central Poland has commenced. Around a thousand men from every county were driven out, virtually every intellectual and landowner; only workers remained, while farmers as well as small merchants and craftsmen were stripped of their property and also turned into workers. […] Their transportation took place in difficult conditions, often in freight cars, and the ride lasted a few days. Many of our relatives and friends went through this bestiality, and many of them, the elderly in particular, died soon after.’ [Dezydery Chłapowski, Potworowscy. Kronika rodzinna (Potworowskis. A Family Chronicle), 2002]

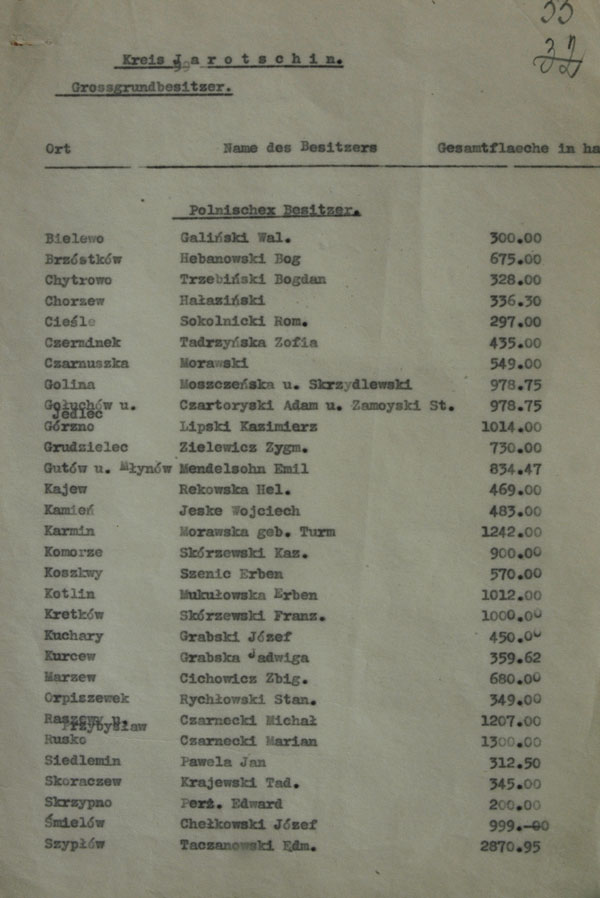

Property of the displaced was confiscated by the Reich on the basis of Himmler’s circular of November 10, 1939. Larger land properties (ca. 3,600 farms) were taken over by the Third Reich’s institutions, which were designated for that purpose.

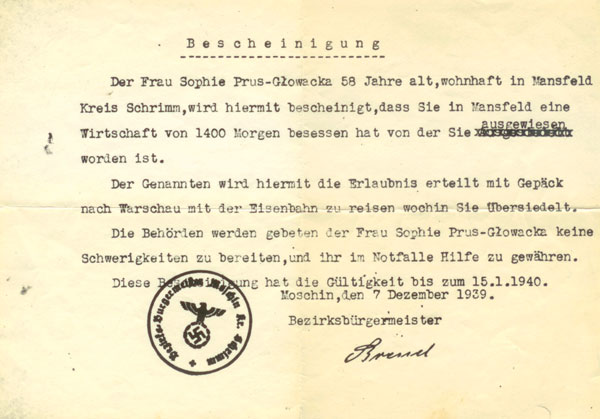

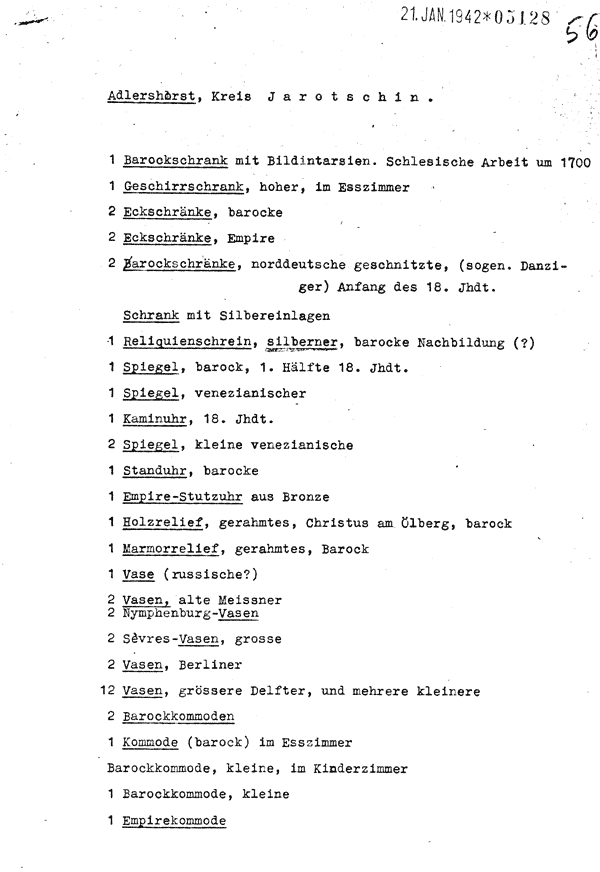

The deportees could only take hand luggage with them, the contents of which included: warm clothes, blankets or duvets, kitchen utensils for eating and drinking, provisions for a few days, and documents. The weight limit was 12.5 kg per person, half of that in the case of children. The remaining clothes and underwear as well as tools used in practicing one’s profession were to be left behind. It was forbidden to take jewellery (excluding wedding rings), works of art, securities, and other items of value.

Roman Mycielski recalls the deportation from the Września-Opieszyn estate in 1939 in the following way: “On December 1 at one a.m. there was a loud banging on the mansion’s door. Someone barged into our room screaming: ‘Dress up!’ […]. In front of the mansion, in deep snow, pale blue in moonlight, a few Germans flounced about, pounding on the door with the butts of their rifles and screaming something I obviously could not understand […]. Finally one of the servants let them in and the mansion was filled with Germans, shouting, brandishing their rifles, and running around all the time. One could make out orders through the uproar: ‘We are to leave the mansion in half an hour, taking only the things we can carry. We cannot take money or other valuables […]’ . Half an hour later, my grandmother, my mom, Izabela [Mycielski, sister of the memoir’s author], and I were standing in the snow in front of the mansion. We carried a few things—I had a school bag on my back, filled with some things, in one hand I carried a small pillow wrapped in a blanket, in the other, my biggest, beloved teddy bear, which I managed to grab in the last moment. Unfortunately we did not take anything to eat […]. The Germans urged the four of us on from the palace through the park and fields, as we waded through the deep snow; the night was freezing. [Roman Mycielski, Rok 1939 w Wielkopolsce. Cz. 3. Wysiedlenie (Year 1939 in Greater Poland. Part 3. Deportation), 2006]